It was Gary Johnson’s 18th birthday on March 31, 1972, when he made his first visit to the eye clinic at the University of Minnesota to participate in a study on the most common diabetic eye disease, retinopathy. He had lived with Type 1 diabetes for 16 years by that point and began having vision problems a couple of years earlier. “They told me I’d be blind within five years and I’d be on dialysis, have a kidney transplant or be dead within seven years,” Johnson remembers. Today, at 63, the semi-retired Bloomington, Minn., resident and Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Minnesota member has stable vision and leads an incredibly active, healthy life. You might find him at a local ice rink reliving his amateur hockey league days, running up the steps at Minnehaha Regional Park—or hula-hooping at a Minneapolis block party. Johnson has seen his share of bumps, bruises and surgeries from a life of sports and adventure, but you’ll never hear him complaining about the disease that 45 years ago was predicted to take his life—the diabetes he’s relentlessly managed for 61 years. “I might have health problems,” he says, “but they’re not diabetes.” Johnson is among an estimated 30 million adults in the United States living with diabetes (Type 1 and 2), according to the latest National Diabetes Statistics Report. He is one of roughly 320,000 Minnesota adults diagnosed with the disease and a powerful example of the ability to live a happy, healthy life through proper diabetes management. But because of the often sneaky symptoms associated with Type 2 in particular, diabetes is often mismanaged, or not managed at all. Roughly one in four diabetics do not know they have the disease, and another one in four are over the age of 65. Understanding the warning signs and what to do about them is key to prevention and avoiding diabetes complications.

DIABETES BREAKDOWN

Back when Johnson rode his bike all over Minneapolis with his friends, he used to pack sugar lumps and Circus Peanuts for cases of low blood sugar, causing his buddies to say they wished they were diabetic so they could eat candy. Later in life, working in a lab as a biochemist, he would get comments from colleagues confused about whether he needed an insulin injection or sugar. “It’s kind of frustrating because the general public doesn’t understand that if someone needs help to the point where they can’t give it themselves, they might do the wrong thing and it could be catastrophic in that situation,” Johnson says. Understanding the disease for personal prevention and management is just as important. Both Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes involve the body’s inability to control blood-sugar levels, but they are quite different otherwise. Here’s an overview, based on information from the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and Mayo Clinic:

Type 1 is an autoimmune disease that affects about 1.25 million Americans and is usually diagnosed in children and young adults. Type 1 diabetics do not produce insulin, a hormone the body needs to get glucose—broken down sugars and starches—from the bloodstream for energy. Type 1 can cause kidney damage (neuropathy), nerve damage (especially in the legs and feet), damage to blood vessels in the eyes (retinopathy), heart and blood vessel disease, skin and mouth conditions, pregnancy problems, and ultimately life-threatening complications if not managed properly.

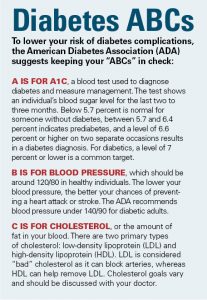

Type 2 accounts for the vast majority of diabetes nationwide and usually develops later in life. It creates a condition in which the body resists insulin, initially prompting the pancreas to make more to compensate. But over time the pancreas can’t keep up, allowing glucose to build, sapping cells of energy and leading to the same complications as those found in Type 1 diabetes. REDUCING RISK Genetics play a role in the development of both types of diabetes, with Type 1 individuals commonly inheriting risk factors from both parents, but the triggers for that disease are still largely unknown, according to the ADA. The links to family history are stronger in Type 2 diabetes, with both genetics and lifestyle choices passed along from parents playing roles. Whereas the onset of Type 1 is usually sudden, Type 2 develops slowly and often silently. Matt Petersen, managing director of medical information for the ADA, says common Type 2 diabetes warning signs—excessive thirst, frequent urination, blurry vision, fatigue, weight loss— in older adults are commonly misconstrued as symptoms that simply come along with getting older. Anyone with these symptoms, he says, should consult their doctor. The ADA recommends Type 2 diabetes screenings every three years for individuals age 45 and older. In addition to age, Petersen notes that obesity, inactivity and high blood pressure are also common Type 2 risk factors. Most of these can be controlled through diet and lifestyle changes. Even genetically at-risk individuals (those with a diabetic parent or sibling) can decrease their chances of developing the disease through a healthy lifestyle.

MANAGEMENT

Insulin therapy is the primary treatment for Type 1 diabetes, but careful consideration of food intake and activity is needed to calculate insulin injections, which can be administered manually or with a pump. Johnson says the arrival of the at-home glucose monitor in the late 1970s saved his life by allowing him to check his blood-sugar levels throughout the day, especially before and after meals and during exercise. He learned to give himself insulin shots at the age of 4, but relied on how he felt, along with supportive parents and friends, before the meter came along. He believes the ability to accurately monitor his blood sugar and properly dose insulin early on might have prevented his eye problems. Johnson also now uses an insulin pump that he programs as needed and a continuous glucose monitor (CGM). He continues to check his glucose levels about eight times a day and also uses glucose tablets in lieu of sugar lumps and Circus Peanuts if he experiences a low-sugar episode. For Type 2 management, a balanced, healthy diet and physical activity are the primary treatment methods. Insulin can also be used to help treat Type 2 and about a dozen types of oral medications are available. That’s up from only a couple of medications 20 years ago, Petersen says. “Different medications work better or worse in particular individuals so someone with Type 2 diabetes will need to work with their doctor on what’s going to work best for them,” he says. Metformin, which helps the body respond to insulin and slows the production of glucose, is a commonly used medication among Type 2 diabetics, such as Carrie Boe, 50, of Minneapolis, who has lived with Type 2 for 25 years. But Boe, who had a family history of diabetes and struggled with management of the disease for years, says diet and exercise changes dramatically reduced her symptoms and dependence on medication in recent years. She says she weighed about 350 pounds before committing to hiring a personal trainer at age 45, and has since lost more than 100 pounds. Inspired by her progress and how much better she felt, she became a certified health coach and now works with Twin Cities diabetics to help them live healthier lives. The number-one key to managing the disease, she says, is having the right mindset. “If you’re waiting for motivation, change is not going to happen,” she says. “You have to make it happen.”

GETTING INSPIRED

Johnson started attending monthly Life with Diabetes meetups, offered through Boe’s SuperStrongDiabetics coaching services, about a year ago. The support community allows Type 1 and Type 2 diabetics to share their experiences, learn from each other and find inspiration to better manage the disease. “He has been a wonderful inspiration for both our Type 1s and our Type 2s, to see someone who has successfully managed this disease and lived a full, active and long life,” Boe says. Johnson says he’s not too old to find new ways to improve his health—he’s made a point of doing that since he was a teenager, when he received the first of what would ultimately be about 40 eye operations. He considers himself a fighter who will never give in to the disease he’s spent a lifetime with. And if he can impart that attitude on other diabetics, he’s happy to do so. “I have never felt sorry for myself,” Johnson says. “If you could live to be 150 and never had to eat or drink or sleep, you still could not begin to do everything you wanted to do, and experience everything you wanted to experience. You have to make priority choices and the first thing to go out the window is self-pity. I enjoy life.”